Zen Individualialism

There is still another feature of Zen which assumes great significance in relation not only to moral life, but also to aesthetic expression. That feature is individualism. The Zen enlightenment is a highly refined abstraction. This abstraction is not, however, a mere negation of the concrete or a teaching of nothingness, but a transcendent view of the world. Its attainment consists in detachment from commotion and in steadfastness amid surrounding changes. The mind of a Zenist may be compared with a rock upstanding from the depths of the sea, resisting and defying the perpetual movement of the waves; it is also like the pure moonlight, sometimes obscured by clouds, yet never losing its purity or its power of beautifying whatever it illuminates. Strength to meet weal and woe equally, to enjoy life and nature in absolute composure and lofty calmness, — such is the aim of the Zen practice. Determination bordering on stubbornness, tranquility akin to apathy, self-continence mistakable for indifference, — therein were manifested the results of the individualistic culture of Zen, as a method of achieving a union of the individual soul with the cosmic spirit, Zen training manifested itself in art of a transcendental kind.

There is still another feature of Zen which assumes great significance in relation not only to moral life, but also to aesthetic expression. That feature is individualism. The Zen enlightenment is a highly refined abstraction. This abstraction is not, however, a mere negation of the concrete or a teaching of nothingness, but a transcendent view of the world. Its attainment consists in detachment from commotion and in steadfastness amid surrounding changes. The mind of a Zenist may be compared with a rock upstanding from the depths of the sea, resisting and defying the perpetual movement of the waves; it is also like the pure moonlight, sometimes obscured by clouds, yet never losing its purity or its power of beautifying whatever it illuminates. Strength to meet weal and woe equally, to enjoy life and nature in absolute composure and lofty calmness, — such is the aim of the Zen practice. Determination bordering on stubbornness, tranquility akin to apathy, self-continence mistakable for indifference, — therein were manifested the results of the individualistic culture of Zen, as a method of achieving a union of the individual soul with the cosmic spirit, Zen training manifested itself in art of a transcendental kind.

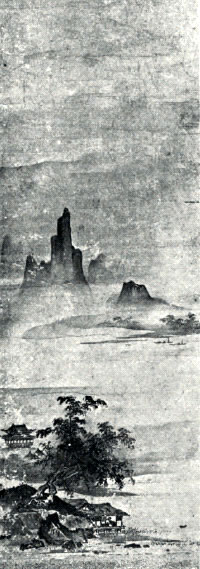

A Chinese Landscape By Josetsu, Early Fifteenth Century Japanese, Ashikaga Idealistic School In the Museum of Fine Arts , Boston. Painted in ink on paper and mounted as a kakemono.

Naturalism and intuitionism enabled the Zenist not only to absorb the serenely transient beauty of nature, but also to express it, distinct from human passions and interests, in placid dignity and pure simplicity; while individualism, a necessary consequence of Zen practice, found expression in a vigor and freshness of artistic treatment implying always a touch of original genius. Thus the aesthetic sense developed by the culture consisted essentially in disinterested observation and penetrating insight which produced a feeling of intimacy with the universe and caused man to mould his life and taste in accordance with the "air-rhythm" of nature.

The 'Men of the Mountains", the Taoist hermits and sages, depicted by Zen painters are taken from the semi-legendary poets, hermits and sages of Taoism, whose sentiment toward nature has, in this way, permeated the art and life of the Japanese, especially since the fourteenth century. As represented in the pictures, one or more of these Immortals may exhibit the weird art of floating through the sky; another projects his own image from his mouth; another causes a horse to come out of a gourd. Yet they were admired not as mere magicians but as embodiments of the attainment in Zen through which an adept could spiritually perform similar feats, such as the act of ''inhaling and exhaling the whole universe at one breath," as it is called. They were not supernatural men; on the contrary the "Men of the Mountains" were children of nature, and are shown amusing themselves in nature. Plates depict two such beings, Chinese poets of the seventh century. The one, Han-Shan, or "Cool-Hill," has a blank scroll, implying that he reads the unwritten book of nature. The other, Shih-Te,* or "Picking-up," holds a broom, — the broom of insight, of wisdom, of transcendence, — with which to brush away all the dusts of worry and trouble. To read the book of nature: that is the ideal of Zen naturalism and intuitionism; to sweep off all troubles: that is the motto of Zen individualism and transcendentalism.

The grandeur or tranquility of nature seen through the spiritual eyes of one purified by long training in Zen; the changes of life and season absorbed into the calm depth of contemplation; — such impressions the painter strove to catch with simple, bold strokes of his brush and with little color. Distant hills like shadows; water marked out by a few ripples; sails and boats just dotted in; rocks and trees drawn with a few touches; these make up a landscape. Human figures are often added to the scene, and appear to be gazing beyond the expanse of water, or loitering in the moonlight, or looking up at the cliffs and waterfalls. They are meant to be Taoists or Zenists whose presence in the picture shows that they are seeing the view as reflected in their purified minds.

The grandeur or tranquility of nature seen through the spiritual eyes of one purified by long training in Zen; the changes of life and season absorbed into the calm depth of contemplation; — such impressions the painter strove to catch with simple, bold strokes of his brush and with little color. Distant hills like shadows; water marked out by a few ripples; sails and boats just dotted in; rocks and trees drawn with a few touches; these make up a landscape. Human figures are often added to the scene, and appear to be gazing beyond the expanse of water, or loitering in the moonlight, or looking up at the cliffs and waterfalls. They are meant to be Taoists or Zenists whose presence in the picture shows that they are seeing the view as reflected in their purified minds.

Shih-Te (Jittoku) By Gei-ami, Fifteenth Century Japanese, Ashikaga Idealistic School In the Museum of Fine Arts , Boston The recluse poet is here shown smiling at the moon. His besom lies on the ground at his feet. Painted in ink on paper and mounted as a kakemono.

tThe Zen Practice of Meditation vvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvThe Secularization of Zen Art u