SYMBOLIC REPRESENTATIONS

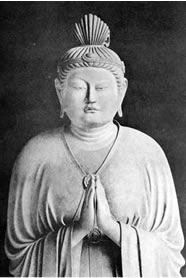

Dai-Itoku-myowo, the Great Majestic Power Japanese, Tenth Century In the Museum of Fine ArU, Boston Although his typical figure has six faces which exhibit the six miraculous powers, and six arms which purify the six resorts of transmigration, he is shown in this wood sculpture of the Fujiwara period with but three faces and two arms, the latter joined in the mystic form of the one-pointed vajra.

Dai-Itoku-myowo, the Great Majestic Power Japanese, Tenth Century In the Museum of Fine ArU, Boston Although his typical figure has six faces which exhibit the six miraculous powers, and six arms which purify the six resorts of transmigration, he is shown in this wood sculpture of the Fujiwara period with but three faces and two arms, the latter joined in the mystic form of the one-pointed vajra.

The characteristics of the Buddhist deities are represented chiefly by facial expression and bodily posture. A bodily expression is usually understood to be the natural way of moving the muscles of the face or other parts of the body, in response to the impulses of thought or feeling. Doubtless the foregoing is enough to indicate on what considerations the figures depicted in Buddhist art are based. Many of them show expressions common to every one; others conform to the usage of Asiatic peoples, and some others exemplify the more special mode of expression in suppression. This last is best seen in the figure of Fudo, a furious manifestation of the Great Illuminator, to whom allusion has already been made. His name means immobile or immovable, and he sits or stands, firm and motionless, surrounded by leaping flames. His arms are bent toward his body; his hands grasp tightly a sword and a rope; there is no attempt to suggest action; and yet the whole posture is expressive of the utmost energy. Another instance may be seen in the profound contemplation of the Great Illuminator. His whole body is in a perfect equipoise; his hands rest on his knees, his head is inclined a little forward, and his face is calm ''like the moon." There is no expression in the active sense, yet the figure tells of a fullness of wisdom which can be poured out without end. It is an infinite eloquence in silence. Nevertheless, the paradox implied in such a phrase is not real, inasmuch as the Buddhists have always trained themselves to reserve emotion and to restrain expression within the bounds of potentiality.

In this connection let me say a few words about the position of arms and hands, and its influence upon mental states. An eminent psychologist has said that a man does not weep because he is sad but is sad because he weeps; and though this cannot be a whole truth, it is an interesting remark in its bearing on the relation of bodily posture to mental conditions, which, in turn, is one way of explaining the significance of the various attitudes of body, arms and hands associated with deities who are presented in accordance with the Buddhist iconography. If the body, whether standing or sitting, be held erect, the palms joined before the breast, and the position calmly maintained ; or if one hand be grasped by the other, as in the figure of the Great Illuminator, and the respiration be quietly controlled; or if all the muscles of the body be contracted, and the formidable facial expression of the Immobile Deity be assumed ; — then, by imitating these and other postures in conformity with the rules of Shingon, it will become possible gradually to acquire the mental atmosphere, the powers and the virtues associated with these deities. This point is emphasized in order to show that the various attitudes ascribed to the deities and represented in painting and sculpture are not mere arbitrary conventions, but realistic embodiments of the postures which were assumed by the Buddhists in the course of their mental training. From this point of view it may be said that the Buddhist art is a significant achievement of genius fostered by a religion of systematic mysticism, expressed in association with various methods of mental training and based upon the ideas and ideals of a vast cosmotheistic system.

FUGEN, THE All-PERVADING WISDOM Artist unknown Japanese, Early Twelfth Century In the Museum of Fine Arts , Boston He appears here as the Giver of Life, in a special manifestation known as Fugen En-myo, the Indestructible Existence, a consequence of wisdom and insight. The elephant he rides is standing on the Indestructible Wheel of the cosmos, and has three heads, each provided with six tusks which are sometimes explained as symbolic of the subjugation of the six sources of temptation, — i. e., the five senses and the will. Ranged in pairs on either side are the four Guardian Kings. The picture, originally one member of a triptych, dates from the Fujiwara period and conforms, for the most part, to the iconographical rules of Shingon Buddhism. Painted in colors on silk and mounted as a panel.