Zen Buddhism: Naturalism and Individuality

In this landscape in black and white, — like some view seen in a dream, there are suggestions of rocks, trees and a beach in the foreground, all drawn with a few strokes, as if the artist had to spare both ink and brush. In the background appear faint shades, probably distant precipices. Modern critics would classify this sketch among the works of impressionism or idealism, and such classification may well be correct as far as it goes. But we are concerned here less with the class to which a painting belongs than with the religious motive which inspired the painter. In the present instance the artist was a Buddhist monk, Sesshu (1420-1506), one of the greatest of Japanese painters; and this landscape was given by him to one of his disciples in recognition not only of proficiency in art, but also of spiritual attainment in Buddhist training. How, then, and in what sense could this be a religious painting.

In this landscape in black and white, — like some view seen in a dream, there are suggestions of rocks, trees and a beach in the foreground, all drawn with a few strokes, as if the artist had to spare both ink and brush. In the background appear faint shades, probably distant precipices. Modern critics would classify this sketch among the works of impressionism or idealism, and such classification may well be correct as far as it goes. But we are concerned here less with the class to which a painting belongs than with the religious motive which inspired the painter. In the present instance the artist was a Buddhist monk, Sesshu (1420-1506), one of the greatest of Japanese painters; and this landscape was given by him to one of his disciples in recognition not only of proficiency in art, but also of spiritual attainment in Buddhist training. How, then, and in what sense could this be a religious painting.

A Landscape By Sesshu, 1420-15o6 Japanese, Ashikaga Ideaustic School In ihe Imperial Museum , Tokyo Painted in ink on paper and mounted as a kakemono.

In order to prepare for the solution of this question, I shall ask consideration for another ink drawing.

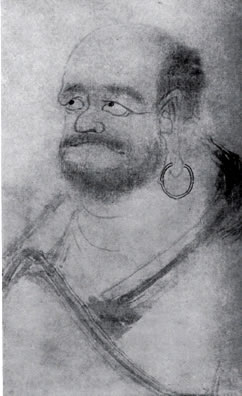

Here you see the face of a man who seems to be looking at something intently. His mouth is tightly closed, whether in a sarcastic smile or in determined resolution, one can hardly tell, but surely in perpetual silence. A few rough, vigorous strokes indicate that his hands are folded under a robe which covers his shoulders and leaves his breast exposed. Simplicity and boldness of composition and suggestiveness of line are apparent; and these technical characteristics are so combined in the singular expression of the figure, as to indicate reserves of strength behind the outward composure. The picture is meant to be a portrait of Bodhidharma, the first patriarch of Zen Buddhism in China.

Here you see the face of a man who seems to be looking at something intently. His mouth is tightly closed, whether in a sarcastic smile or in determined resolution, one can hardly tell, but surely in perpetual silence. A few rough, vigorous strokes indicate that his hands are folded under a robe which covers his shoulders and leaves his breast exposed. Simplicity and boldness of composition and suggestiveness of line are apparent; and these technical characteristics are so combined in the singular expression of the figure, as to indicate reserves of strength behind the outward composure. The picture is meant to be a portrait of Bodhidharma, the first patriarch of Zen Buddhism in China.

Ideal Portrait of Bodhidharma First Patriarch of Zen Buddhism in China By Men Wu-kuan (Mon-mukwan) Chinese, Thirteenth Century Owned by Myoshin-jit near Kydio, and now deposited in the Imperial Museum , Kyoto

He came to that country in the sixth century, and from his life and teachings Japanese Buddhism, after the thirteenth century, derived its inspiration. This portrait was undoubtedly based upon an older one taken from life; but in all probability such considerations did not greatly concern the artist, whose object was to show the face and posture typical of a man who had attained a lofty spiritual training in the sect of Zen. It is believed also that the simple technique and bold expression are in real accordance with the spirit of that teaching, as well as with the ideal look of the patriarch. As in the landscape we have just considered, so in this portrait there prevails a mood of deep serenity resulting from the spiritual attainment and mental purity which were identified with the life movement of the spirit. This affinity of the artist's mind for the rhythm of the world gives to his work an air of inwardness. According to these painters, a picture should be the soul of nature brought to a focus before the purified, spiritual eyes of man, — the cosmic spirit embodied in a little space through a mind in full grasp of the cosmos; and thus it is the pulsation of the cosmic rhythm in the individual mind that gives the serenity of the " air-rhythm " * and the pure outline of the "wind-frame." *

vvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvThe Zen Practice of Meditationuv